Você provavelmente já ouviu isso mil vezes: “Levante peso, coma proteína, ganhe músculos”. Mas eis o que a maioria dos treinadores nunca menciona: os mecanismos biológicos reais que promovem o crescimento muscular são muito mais complexos do que essa fórmula simplista. Especificamente, entender o diferença entre hipertrofia e hiperplasia Essa é a diferença entre treinar de forma inteligente e treinar às cegas.

Para ser direto: se você acha que o crescimento muscular se resume a uma única coisa, está perdendo oportunidades de ganho. A ciência mostra que hipertrofia versus hiperplasia Não são mecanismos concorrentes. São processos complementares, e saber como treinar para ambos muda fundamentalmente a forma como você programa o treinamento de resistência. Isso não é mera formalidade acadêmica — é conhecimento prático que altera os resultados.

Vamos analisar o que realmente acontece dentro dos seus músculos quando você treina e, mais importante, como medir e otimizar ambos. hipertrofia muscular e hiperplasia muscular Para obter os melhores resultados.

BAIXE O APLICATIVO SPLEEFT AGORA PARA iOS, ANDROID E APPLE WATCH!

O que você realmente precisa saber sobre crescimento muscular.

Antes de falarmos sobre mecanismos específicos, vamos estabelecer uma distinção crucial: hipertrofia e hiperplasia Estão descrevendo fenômenos diferentes, e ambos ocorrem em resposta ao treinamento — apenas com gatilhos e cronogramas diferentes.¹

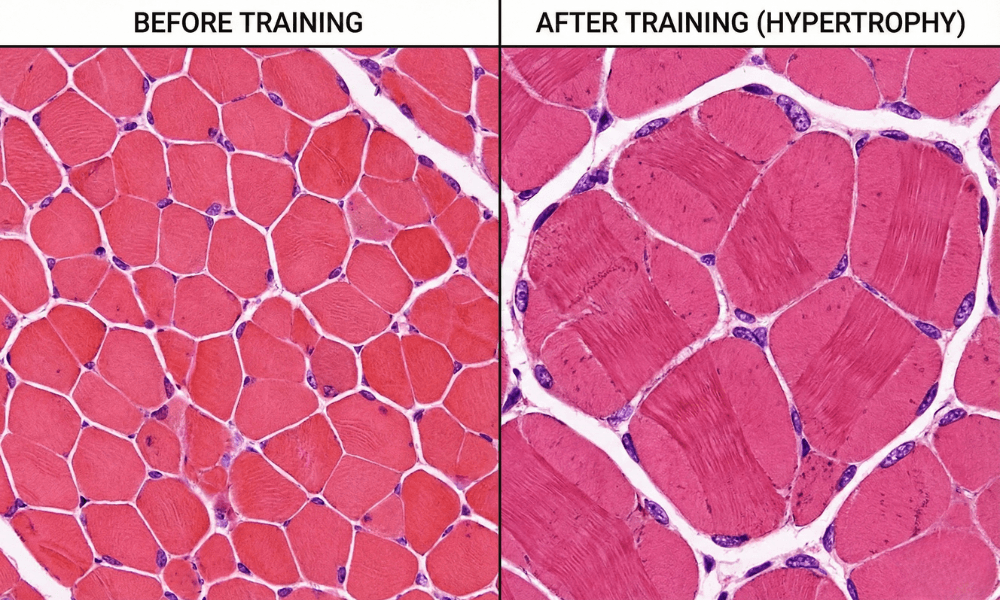

Hipertrofia Significa que as próprias fibras musculares aumentam de tamanho. Mais proteínas contráteis se acumulam dentro de cada fibra. É isso que a maioria das pessoas imagina quando pensa em "crescimento muscular". É o aumento no tamanho das fibras musculares.²

Hiperplasia é fundamentalmente diferente. Significa um aumento no número de fibras musculares. Isso acontece quando as fibras musculares existentes se dividem ou quando as células satélite (células-tronco musculares) se fundem para criar novas fibras.³ Por décadas, os profissionais de fitness descartaram a hiperplasia como irrelevante em humanos. Pesquisas recentes provam que eles estavam errados.

Eis por que isso é importante: um músculo que cresceu de 50 para 55 fibras (por hiperplasia) sempre terá uma vantagem de capacidade sobre um músculo do mesmo tamanho, mas com o mesmo número de fibras (hipertrofia pura). Mais fibras, mesmo que ligeiramente menores, significam maior capacidade total de produção de força e maior potencial de crescimento futuro.¹

Hipertrofia: o principal mecanismo de crescimento em humanos.

Hipertrofia versus hiperplasia Na maioria dos contextos de treinamento de resistência, não se trata realmente de uma situação de "versus". A hipertrofia predomina. Após a puberdade, os humanos perdem a capacidade de gerar novas fibras musculares com facilidade. Em vez disso, crescemos principalmente aumentando o tamanho das fibras existentes.² Essa é a adaptação padrão.

Como a hipertrofia realmente funciona

Quando você trem de resistência, várias vias moleculares são ativadas:

Sinalização mTORC1A via de sinalização mTOR (alvo da rapamicina em mamíferos) é o principal regulador da síntese proteica. Tensão mecânica, estresse metabólico e danos musculares ativam o mTORC1, que sinaliza aos ribossomos para produzirem mais proteína muscular.²⁴

aumento da síntese proteicaSuas células musculares literalmente produzem mais proteínas contráteis (actina e miosina). Essa é a base física do crescimento das fibras musculares. Essa síntese elevada continua por 24 a 48 horas após o treino, e é por isso que a recuperação é importante.⁴

Adição de mionúcleosÀ medida que as fibras crescem, elas precisam de mais mionúcleos (os núcleos celulares dentro das fibras musculares). As células satélite se fundem com as fibras existentes para doar seus núcleos. Essa é uma parte crucial — e frequentemente negligenciada — da hipertrofia sustentável.³ Sem mionúcleos suficientes, as fibras não conseguem continuar crescendo além de um determinado limite de tamanho.

Remodelação da matriz extracelularO tecido conjuntivo que envolve as fibras musculares também se adapta. Essa remodelação estrutural fornece o "andaime" que sustenta as fibras maiores e melhora a transferência de força.

Que tipo de treino proporciona a hipertrofia máxima?

A pesquisa é clara: hipertrofia A resposta mais robusta é obtida com cargas moderadas (65-85% 1RM) com faixas de repetições moderadas a altas (6-15 repetições por série) realizadas até próximo da falha muscular, com 1-3 minutos de descanso entre as séries.² Um volume maior (mais séries e repetições no total) produz maior hipertrofia quando a recuperação é adequada.

Fundamentalmente, o tempo sob tensão é crucial. As fases excêntricas (descida do movimento), em particular, impulsionam a hipertrofia porque maximizam a tensão mecânica na fibra muscular. É por isso que tempos controlados — 3 a 5 segundos na fase excêntrica — produzem hipertrofia superior em comparação com as fases negativas rápidas e descontroladas.⁴

A velocidade com que você executa as repetições também influencia a resposta hipertrófica. Pesquisas mostram que velocidades controladas com qualidade consistente nas repetições produzem hipertrofia mais confiável do que repetições explosivas máximas. No entanto, aqui está a nuance prática: manter uma velocidade constante da barra ao longo das séries — usando medições objetivas — garante que você permaneça na zona de intensidade pretendida e não entre em um ritmo de esforço intenso dominado pela fadiga, o que reduz a eficiência da hipertrofia.⁵

Hiperplasia: O Mecanismo de Crescimento Subestimado

Agora, é aqui que entra a compreensão. hiperplasia muscular O crescimento torna-se crucial. Durante décadas, os livros didáticos afirmavam que a hiperplasia era irrelevante em humanos. Essa afirmação está desatualizada. Pesquisas recentes — particularmente utilizando técnicas avançadas de imagem e biópsia — mostram que hiperplasia muscular contribui significativamente para o crescimento muscular, especialmente sob condições de carga extrema.³⁶

Quando ocorre, de fato, a hiperplasia?

Hiperplasia Parece ocorrer principalmente sob duas condições:

Sobrecarga mecânica extrema e prolongadaQuando os músculos são submetidos a uma tensão mecânica sustentada e muito alta (como em modelos de ablação sinergista em animais ou treinamento extremo em fisiculturistas de elite), pode ocorrer a divisão das fibras. Este é um processo no qual as fibras musculares individuais se dividem literalmente em duas fibras menores, em vez de continuarem a crescer.⁶

Ativação e fusão de células satéliteSob estímulo de treinamento suficiente, as células satélite são ativadas, proliferam e se fundem com as fibras musculares existentes. Isso adiciona mionúcleos às fibras, o que permite um maior crescimento. Algumas evidências sugerem que, em casos de hipertrofia extrema, essas regiões recém-nucleadas podem eventualmente se desenvolver em segmentos de fibras funcionalmente independentes.³⁶

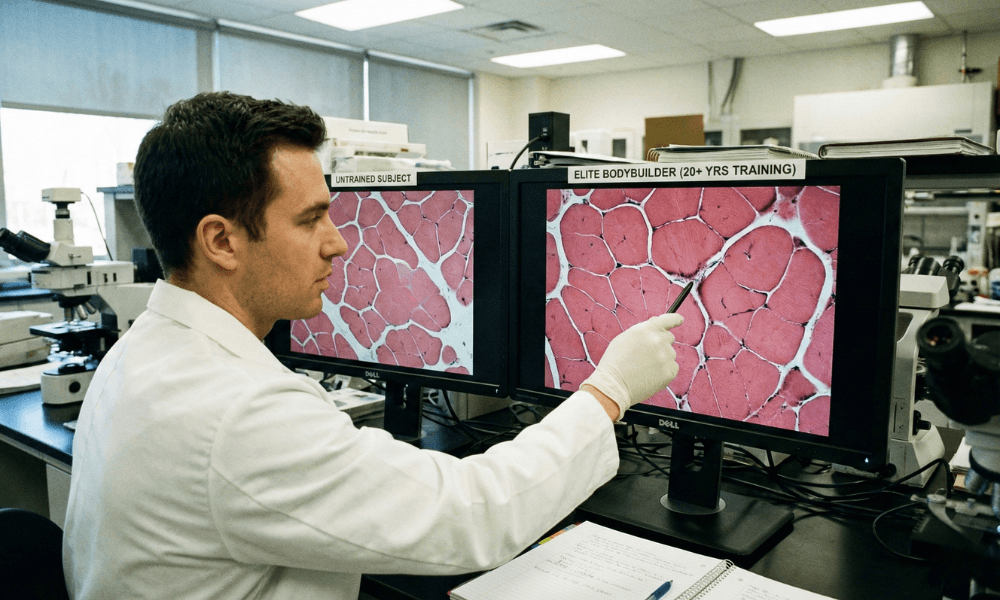

Observação de Atletas de Elite

Estudos comparativos entre fisiculturistas de elite e indivíduos não treinados mostram algo interessante: os fisiculturistas geralmente têm um número significativamente maior de fibras musculares do que pessoas não treinadas, mesmo levando em consideração as diferenças de tamanho corporal.⁶ Isso sugere que o treinamento extremo e prolongado realmente produz hiperplasia muscular adaptação ao longo dos anos.

No entanto — e isto é crucial — essa diferença na quantidade de fibras musculares resulta principalmente de décadas de treinamento consistente e de alto volume, combinadas com nutrição ideal e, frequentemente, suporte farmacológico (que amplifica drasticamente a ativação das células satélite). Não é algo que acontece em um único ciclo de treinamento.

O debate sobre a divisão da fibra

Eis o que pesquisas recentes esclareceram: as fibras musculares podem sofrer hiperplasia por meio de ramificação ou divisão.⁶ Quando uma fibra cresce extremamente sob tensão mecânica extrema, ela pode desenvolver um ponto de ramificação. Em vez de continuar como uma única fibra maciça, ela se divide em duas fibras, cada uma com seu próprio aglomerado de núcleos. Isso parece ser uma resposta fisiológica às restrições na difusão de oxigênio e na logística metabólica — uma vez que uma fibra atinge um tamanho crítico, a organização por divisão torna-se mais eficiente do que o aumento contínuo de tamanho.⁶

Isso se aplica ao treino normal de academia? Provavelmente não de forma significativa. Mas com cargas extremas (levantamento de peso de elite, fisiculturismo de elite) mantidas por anos, a divisão das fibras musculares provavelmente contribui de forma significativa para a massa muscular superior que esses atletas alcançam.

Comparando Hipertrofia e Hiperplasia: Uma Análise Prática

| Característica | Hipertrofia | Hiperplasia |

|---|---|---|

| Mecanismo | Aumento do tamanho das fibras por meio da síntese de proteínas | Aumento no número de fibras por meio de divisão ou fusão de células satélite. |

| Estímulo | Cargas moderadas a pesadas, repetições moderadas a altas, próximo à falha muscular. | Tensão mecânica extrema, volume muito elevado, sobrecarga prolongada |

| Linha do tempo | Rápido (ganhos visíveis em 4 a 8 semanas) | Lento (meses a anos) |

| Prevalência em Humanos | Mecanismo primário de crescimento (>90% de ganhos) | Mecanismo secundário (~10% de ganhos em atletas treinados) |

| Método de medição | Área da secção transversal da fibra por meio de biópsia | Contagem de fibras por meio de biópsia ou análise de secção transversal. |

| Fator limitante | Densidade de mionúcleos, capacidade de síntese proteica | Disponibilidade de células de satélite, tolerância a cargas extremas |

| Reversibilidade | Parcialmente reversível com o destreinamento. | Em grande parte permanente, uma vez estabelecido. |

| Frequência de treinamento | 2 a 4 vezes por semana por músculo (ideal) | Requer um volume sustentado e muito elevado. |

A diferença entre hipertrofia e hiperplasia na programação prática

Aqui é onde o diferença entre hipertrofia e hiperplasia Na verdade, isso importa para o seu treinamento: você não pode programar a hiperplasia de forma confiável. Mas você pode, sim, otimizar a hipertrofia sem inibir ativamente qualquer adaptação hiperplásica em potencial.¹

A maioria dos fisiculturistas e atletas de força sérios treinam intuitivamente de maneiras que, ao longo do tempo, provavelmente estimulam pequenas quantidades de hiperplasia juntamente com uma hipertrofia substancial. Treinamento de alto volume com cargas pesadas, mantido por anos, é a receita.

A fórmula é a seguinte:

8 a 15 séries por músculo por semana, distribuídas em 2 a 4 sessões

Cargas moderadas (65-80% 1RM) para permitir repetições mais altas

3-5 segundos de ritmo excêntrico para tempo máximo sob tensão

Descanso de 1 a 3 minutos. entre as séries para permitir a recuperação, mantendo o estresse metabólico

Consistência ao longo dos anos, não semanas

Essa programação produz a grande maioria dos ganhos por meio de hipertrofia muscular (aumento do tamanho da fibra), com potencial para pequenas quantidades de hiperplasia muscular adaptação se o volume se acumular o suficiente ao longo do tempo.

Utilizando a medição da velocidade para otimizar a hipertrofia

Eis a aplicação prática que muda tudo: Ao treinar para hipertrofia versus hiperplasia Para ganhos puramente hipertróficos, a consistência na qualidade das repetições influencia drasticamente os resultados. As repetições 1 a 3 de uma série geralmente são diferentes das repetições 8 a 10 da mesma série. As primeiras repetições são mais precisas; as últimas, mais lentas. Essa diferença na velocidade das repetições indica algo importante sobre o estímulo do treino.¹

Usando um treinamento baseado em velocidade aplicativo O Spleeft faz isso de forma objetiva. Quando você programa, por exemplo, “3×10 @ 70% 1RM com velocidade controlada”, o Spleeft permite que você veja exatamente quais repetições mantêm a qualidade do exercício e quais se tornam repetições desgastantes. Se a sua primeira repetição se move a 0,7 m/s e a sua décima repetição se move a 0,35 m/s, você está treinando qualidades diferentes. As primeiras repetições priorizam a força; as últimas repetições priorizam o estresse metabólico.⁵

Especificamente para hipertrofia, pesquisas sugerem que manter uma perda de velocidade de 20-30% por série proporciona o estímulo ideal para o crescimento muscular. Isso significa:

Repetição 1: 0,70 m/s

Rep 10: ~0,50-0,56 m/s (uma queda de 20-30%)

Este perfil de velocidade — começando com uma velocidade explosiva controlada e permitindo a perda de velocidade induzida pela fadiga até cerca de 20-30% — produz ganhos de hipertrofia confiáveis. O aplicativo Spleeft monitora isso em tempo real, fornecendo feedback imediato sobre se você está na faixa ideal ou se está forçando excessivamente (perda de velocidade >40%) ou desacelerando com muita facilidade (perda de velocidade <15%).¹⁵

A vantagem prática: em vez de ficar na dúvida se está treinando o suficiente ou demais, você vê os dados. Você ajusta a carga de acordo. Ao longo de semanas e meses, essa precisão se acumula, resultando em hipertrofia visivelmente superior.

FAQs

1. Posso treinar especificamente para hiperplasia sem ser um atleta de elite?

Não em nenhum sentido prático. Hiperplasia muscular O desenvolvimento muscular exige cargas extremas e sustentadas ao longo de anos. Para frequentadores comuns de academia e até mesmo para competidores sérios, a resposta hipertrófica é tão dominante que otimizar para a hipertrofia automaticamente coloca você em posição de aproveitar quaisquer adaptações hiperplásicas que possam ocorrer. Concentre-se no volume, na consistência e na qualidade do treino. A hiperplasia virá como consequência, se tiver que vir.

2. A massa muscular perdida durante o destreinamento retorna mais rapidamente do que o ganho inicial?

Parcialmente. A massa muscular recuperada retorna mais rapidamente do que a adaptação inicial, porque os mionúcleos persistem mesmo quando as fibras encolhem. Suas fibras musculares "lembram" o tamanho que atingiram porque retiveram os núcleos. No entanto, quaisquer ganhos de hiperplasia muscular (Se ocorrerem) são permanentes. Não é possível perder fibras musculares apenas com o destreinamento — seria necessário que houvesse dano muscular real ou atrofia por imobilização.

3. Existe um limite máximo para a hipertrofia?

Do ponto de vista mecanístico, sim. O limite de tamanho das fibras parece estar relacionado à densidade dos mionúcleos. Cada mionúcleo pode suportar uma certa quantidade de citoplasma. Uma vez atingida essa proporção, o crescimento adicional do tamanho torna-se difícil sem a adição de mais mionúcleos por meio da fusão de células satélite. Isso explica, em parte, por que o treinamento contínuo (que desencadeia a fusão de células satélite) é necessário para ganhos sustentados de hipertrofia além da adaptação inicial.

4. Exercícios diferentes produzem proporções diferentes de hipertrofia versus hiperplasia?

Evidências sugerem que exercícios compostos e pesados (agachamentos, levantamentos terra) com extrema tensão mecânica podem favorecer a hiperplasia ligeiramente mais do que exercícios isolados. No entanto, o efeito é pequeno. Treinamento de alto volume com qualquer exercício produz hipertrofia de forma consistente. O exercício específico importa muito menos do que o volume total, a consistência e a sobrecarga progressiva.

5. Como a idade afeta a capacidade de hipertrofia versus hiperplasia?

A hipertrofia permanece responsiva ao longo da vida com treinamento adequado, embora a taxa de ganho diminua com a idade. Adultos mais velhos retêm a capacidade das células satélite, mas apresentam ativação reduzida em resposta ao treinamento. A hiperplasia torna-se cada vez mais improvável com a idade devido à senescência das células satélite. Atletas jovens demonstram respostas mais robustas das células satélite ao treinamento, o que, teoricamente, torna os jovens ligeiramente mais capazes de adaptação hiperplásica, embora o efeito ainda seja pequeno.

Iván de Lucas Rogero

Desempenho Físico MSC e CEO SpeeftApp

Dedicado a melhorar o desempenho atlético e o treinamento de ciclismo, combinando ciência e tecnologia para gerar resultados.

Referências

Murach KA, Bagley JR, Carson RJ, et al. A divisão das fibras musculares é uma resposta fisiológica à sobrecarga mecânica extrema. Biol Rev. 2019;94(4):1519–1559.

Schoenfeld BJ. Os mecanismos de Hipertrofia muscular e sua aplicação no treinamento de resistência. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857–2872.

Maughan RJ, Watson JS, Weir J. Força e área de secção transversal do músculo esquelético humano. J Physiol. 1983;338:37–49.

Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. Relações dose-resposta entre o volume de treinamento de resistência e a massa muscular. Medicina Esportiva. 2017;47(5):955–963.

Israetel MA, Medicina com Halteres. Características individuais de força em todo o espectro força-velocidade e diretrizes de hipertrofia. 2024.

Murach KA, Mobley CB, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Kavazis AN, Lustgarten MS. Mecanismos que regulam a divisão das fibras musculares esqueléticas durante a hipertrofia com alta carga. Células. 2021;10(9):2247.

McDonagh MJN, White MJ, Davies CTM. Efeitos distintos do envelhecimento nas propriedades mecânicas dos músculos dos braços e pernas humanos. Gerontologia. 1984;30(1):49–54.

Aplicativo Spleft. Rastreamento de velocidade para programação de hipertrofia com exercícios de resistência. A integração com o Apple Watch e o iPhone para medição em tempo real da velocidade de repetição permite o ajuste preciso da carga e o direcionamento para zonas de hipertrofia. Disponível em spleeft.app.