Eis a diferença que a maioria dos treinadores não aborda: a diferença entre fazer um exercício de força e fazer um exercício de força. bem. É possível observar dois atletas executando o mesmo movimento — mesma carga, mesma faixa de repetições — e um desenvolverá força superior enquanto o outro estagnará. A diferença quase sempre reside na qualidade do movimento e em como essa qualidade é medida e mantida ao longo das séries.

É aqui que exercícios de força dinâmica Pare de se preocupar apenas em cumprir as tarefas mecanicamente e comece a se concentrar na precisão. Quando você entender como programar rotinas de treinamento de força dinâmica Com feedback objetivo, você para de ter que adivinhar se seus atletas estão realmente treinando ou apenas acumulando fadiga. Da mesma forma, exercícios de condicionamento Os exercícios que complementam o seu treino de força não são acréscimos aleatórios — são componentes estrategicamente integrados que melhoram diretamente o desempenho atlético.

Vamos falar sobre o que é real. treino de força dinâmica Como programar, e mais importante, como medir seu desempenho para saber se está funcionando.

BAIXE O APLICATIVO SPLEEFT AGORA PARA iOS, ANDROID E APPLE WATCH!

O que torna um exercício “dinâmico” e por que isso é importante?

Antes de entrarmos em detalhes específicos exercícios dinâmicos para a parte superior do corpo E, falando em programação, vamos estabelecer o que “dinâmico” realmente significa no contexto de força, porque é mais complexo do que a maioria dos treinadores explica.¹

A exercício de força dinâmica Um exercício dinâmico é qualquer movimento em que os músculos se alongam e encurtam — as fases concêntrica e excêntrica ocorrem simultaneamente. Isso contrasta com os exercícios isométricos, em que os músculos produzem força sem alterar seu comprimento. Agachamentos, levantamentos terra, supino e remadas são exemplos de exercícios dinâmicos. O peso corporal determina a produção de força, a carga externa determina a resistência e os ângulos das articulações determinam a alavancagem.¹

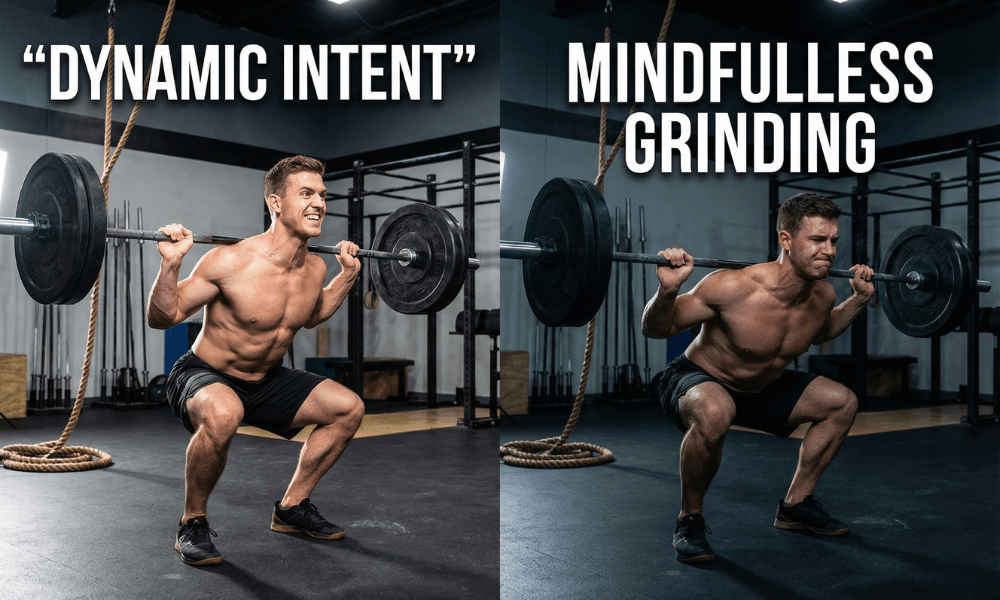

Mas eis a parte crucial que a maioria dos programas ignora: um treino de força dinâmica Não se trata apenas de mover peso do ponto A ao ponto B. Trata-se de mover com velocidade, intenção e consistência. Um agachamento executado lentamente com peso elevado produz adaptações neuromusculares diferentes daquelas produzidas pelo mesmo peso movido explosivamente. Um circuito de exercícios de condicionamento realizado com esforço de 80% produz respostas de fadiga completamente diferentes daquelas realizadas com esforço de 95%.²

Essa distinção é importante porque o estímulo do treinamento — o sinal de adaptação real que seu sistema nervoso recebe — depende de como O movimento é executado, e não apenas a carga externa ou a seleção do exercício. Duas séries idênticas de agachamentos com 85% 1RM podem produzir resultados completamente diferentes se uma for executada lentamente e a outra de forma explosiva com perda de velocidade controlada.²

Os quatro pilares da programação de exercícios de força dinâmica

Real rotinas de treinamento de força dinâmica baseiam-se em quatro princípios fundamentais:

1. Classificação de Padrões de Movimento

Nem todos exercícios de força dinâmica são intercambiáveis. Uma programação eficaz inclui:

Movimentos com predominância do joelho (agachamentos, leg press, afundos)

Movimentos com predominância do quadril (levantamento terra, bom dia, elevação de quadril)

Empurrar com a parte superior do corpo (supino, desenvolvimento militar, paralelas)

Puxada da parte superior do corpo (remadas, flexões na barra fixa, puxadas na polia alta)

Rotacional/antirrotação (Impressão Pallof, rotações de minas terrestres, cortes de cabos)

Transportes e variações de uma perna (transporte de mala, agachamentos divididos, levantamento terra com uma perna só)

Um equilíbrio treino de força dinâmica Inclui exercícios de cada categoria. Pesquisas mostram que a cobertura abrangente de padrões de movimento produz adaptações mais robustas do que a especialização em um único movimento, porque aborda desequilíbrios e desenvolve força funcional em múltiplos planos.³

2. Prescrição de Carga e Intensidade

Exercícios dinâmicos para a parte superior do corpo Tanto o trabalho da parte inferior do corpo quanto o da parte de trás respondem à variação do espectro de carga. A maioria dos treinamentos exige:

Trabalho de força pesada (85-95% 1RM, 1-5 repetições)

Trabalho de hipertrofia (65-85% 1RM, 6-12 repetições)

Potência e velocidade funcionam (40-60% 1RM, intenção explosiva, 3-5 repetições)

Trabalho de condicionamento (40-70% 1RM, 8-15 repetições, estresse metabólico)

Cada zona de intensidade produz adaptações diferentes. O trabalho pesado impulsiona adaptações neurais. O trabalho de hipertrofia impulsiona o crescimento muscular. O trabalho de potência impulsiona a capacidade de velocidade. O trabalho de condicionamento impulsiona a capacidade de trabalho e a resistência muscular.³ Um atleta completo precisa de todas as quatro.

3. Velocidade e Qualidade do Movimento

É aqui que a maioria rotinas de treinamento de força dinâmica falha. A intensidade é prescrita, mas a velocidade real — a rapidez com que o movimento é executado — é deixada ao acaso. À medida que uma série progride, a velocidade diminui naturalmente devido à fadiga. Mas eis o que a maioria dos treinadores não monitora: quanto A diminuição da velocidade indica se você está na zona de treinamento pretendida ou se desviou para algo completamente diferente.⁴

Pesquisas mostram que manter uma velocidade constante da barra ao longo das repetições garante que você esteja treinando a qualidade desejada. Se você programar “3×8 @ 80% 1RM” com o objetivo de hipertrofia, mas na 5ª repetição a barra estiver se movendo a 0,4 m/s (movimento lento e repetitivo), você saiu da zona de hipertrofia e entrou na zona de estresse metabólico. Isso não é necessariamente errado — o estresse metabólico também impulsiona a hipertrofia —, mas é descontrolado e o estímulo adaptativo se torna imprevisível.

4. Integração de exercícios de condicionamento

exercícios de condicionamento Não são exercícios separados do treinamento de força — eles são complementares. Um treino completo treino de força dinâmica Inclui elementos condicionantes que:

Aumentar a capacidade de trabalho (habilidade de manter um alto nível de produção em vários conjuntos de tarefas).

Reduzir os tempos de recuperação entre conjuntos de estímulos sem sacrificar a qualidade.

Promover adaptações metabólicas em conjunto com adaptações de força.

Apoiar a saúde cardiovascular em conjunto com o desenvolvimento neuromuscular.

O treinamento intervalado de alta intensidade (HIIT), o empurrão de trenó, os intervalos de remo e o trabalho em circuito desempenham essa função quando estrategicamente inseridos na programação.²

Seleção de exercícios práticos de força dinâmica

Vamos fundamentar isso em fatos reais. exercícios de força dinâmica Você usaria isso em uma academia. Aqui estão algumas opções baseadas em evidências para diferentes padrões de movimento:

Dominância da parte inferior do corpo: Dominância dos joelhos

| Exercício | Benefício principal | Faixa de carga | Característica de velocidade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agachamento | Força máxima, transferência para saltos | 60-95% 1RM | 0,3-1,0 m/s dependendo da carga |

| agachamento frontal | Ênfase na cadeia anterior, demanda central | 60-85% 1RM | 0,4-0,9 m/s |

| Leg Press | Segurança guiada por máquina, menor risco de lesões | 60-90% 1RM | 0,4-1,1 m/s |

| Agachamento na caixa | Controle de pausa, ênfase concêntrica | 65-90% 1RM | 0,35-0,85 m/s |

Dominância da parte inferior do corpo: Dominância do quadril

| Exercício | Benefício principal | Faixa de carga | Característica de velocidade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levantamento terra convencional | Força máxima na cadeia posterior de todo o corpo. | 70-95% 1RM | 0,2-0,6 m/s |

| Levantamento terra com barra de armadilha | Redução do estresse nas costas, transferência aprimorada | 70-95% 1RM | 0,3-0,8 m/s |

| Bom dia | Isolamento da cadeia posterior, estabilidade da coluna | 40-70% 1RM | 0,4-0,9 m/s |

| RDL de perna única | Equilíbrio unilateral, prevenção de lesões | 20-50% 1RM | 0,6-1,2 m/s |

Empurrar com a parte superior do corpo

| Exercício | Benefício principal | Faixa de carga | Característica de velocidade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supino com barra | Força máxima de pressão, transferência | 65-95% 1RM | 0,3-1,0 m/s |

| Supino com halteres | Controle unilateral, demanda por estabilizadores | 65-85% 1RM | 0,4-1,1 m/s |

| Pressione | Ênfase na potência explosiva, integração das pernas | 50-80% 1RM | 0,6-1,3 m/s |

| Mergulhos | força de pressão com o peso do corpo | 50-80% 1RM* | 0,5-1,2 m/s |

*% 1RM menos relevante; use RPE ou zonas de velocidade

Como elaborar um treino completo de força dinâmica

Eis o que um treino de força dinâmica Na verdade, parece que foi programado para equilibrar todos os elementos:

Dia 1: Ênfase na parte inferior do corpo

Agachamento (Levantamento principal) — 4×4 @ 80% 1RM, visando 0,5-0,6 m/s (zona de força)

Bom dia (acessório) — 3×6 @ 70% 1RM, visando 0,6-0,8 m/s

Agachamento búlgaro (unilateral) — 3×8 por perna @ 60% 1RM

Condicionador finalizador5 séries — 30 segundos de empurrão moderado no trenó + 90 segundos de recuperação

Dia 2: Ênfase na parte superior do corpo

Supino (levantamento principal) — 4×5 @ 82% 1RM, visando 0,5-0,6 m/s

Remada curvada (complementar) — 4×5 @ 82% 1RM, visando puxadas equilibradas

Supino inclinado com halteres (acessório) — 3×8 @ 70% 1RM

Condicionador finalizador: 3 séries de 30 segundos de remo com esforço máximo + 90 segundos de recuperação

Dia 3: Dia de Potência/Velocidade

Limpeza profunda (explosivo) — 5×3 @ 60% 1RM, velocidade máxima

Depth Jump (pliometria) — 4×5 @ peso corporal

Supino com 50% 1RM (trabalho de velocidade) — 4×4 com intenção explosiva, visando >0,9 m/s⁵

Condicionamento de velocidade: 4 sprints de 40m a 95% de esforço + 3 minutos de recuperação

Dia 4: Condicionamento e Recuperação

Aquecimento dinâmico e trabalho de mobilidade

Circuito HIIT: 8 séries de 40 segundos de exercício / 20 segundos de descanso, alternando remo e bicicleta ergométrica.

Transportes com carga: transporte de agricultor, transporte de mala, 3x40m cada

Rolamento de espuma e alongamento

Utilizando a medição da velocidade para otimizar o treinamento de força dinâmica.

Aqui é onde exercícios de força dinâmica Transformar a adivinhação em precisão: Ao medir a velocidade da barra em cada série, você obtém um feedback objetivo sobre se está realmente na zona de intensidade pretendida.⁴

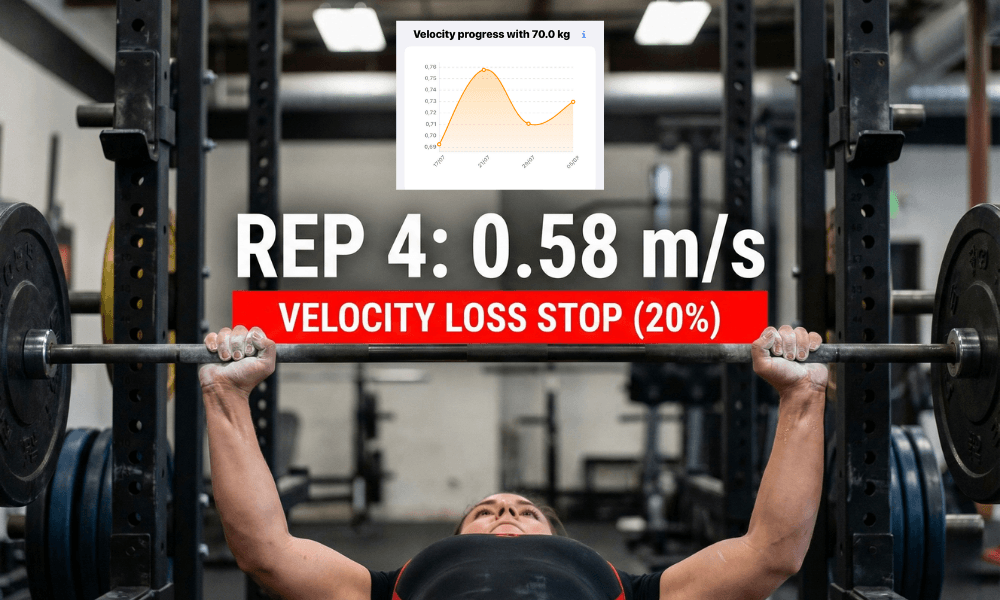

O aplicativo Spleeft faz exatamente isso. Quando você programa um treino de força dinâmica, O Spleeft monitora a velocidade de cada repetição em tempo real. Para um rotina de treinamento de força dinâmica Para atingir a hipertrofia, você pode definir parâmetros como:

Carga: 75% 1RM

Faixa de velocidade alvo: 0,65-0,75 m/s na primeira repetição

Limite de perda de velocidade: 20-30% em todo o conjunto

Ao realizar as repetições:

Rep 1: 0,73 m/s ✓ (dentro do alcance)

Rep 2: 0,70 m/s ✓ (dentro do alcance)

Rep 3: 0,65 m/s ✓ (dentro do alcance)

Rep 4: 0,58 m/s (perda 20% — conjunto final)

Em vez de se esforçar ao máximo na 5ª repetição, você para. Você atingiu o estímulo de hipertrofia desejado sem fadiga excessiva. Na próxima série, carregue um pouco mais e repita. Essa precisão se acumula ao longo de um bloco de treinamento, resultando em resultados visivelmente superiores em comparação com séries de repetições fixas, onde os atletas se esforçam mecanicamente até atingir um número predeterminado.⁴⁶

Para exercícios dinâmicos para a parte superior do corpo Especificamente, manter a consistência na qualidade das repetições é ainda mais crucial, pois a fadiga pode degradar rapidamente a técnica de supino. O feedback de velocidade evita a mentalidade de "estou me esforçando ao máximo, mas vou fazer mais uma", que leva a uma má execução e ao risco de lesões.

Exercícios de condicionamento: o componente negligenciado

Muitos atletas e treinadores subestimam exercícios de condicionamento como algo distinto do treinamento de força. Mas o condicionamento estratégico é essencial para:

Desenvolvimento da capacidade de trabalho — capacidade de sustentar múltiplas séries de alto esforço sem perda de qualidade

Manutenção da força neuromuscular — O trabalho de condicionamento não interfere nos ganhos de força quando programado corretamente.

Saúde metabólica — O condicionamento cardiovascular acompanha o desenvolvimento da força.

Otimização de recuperação — Um treino leve nos dias de descanso pode, na verdade, melhorar a recuperação.

Eficaz exercícios de condicionamento Para atletas de força, inclua:

Trabalho com trenóEmpurrões de trenó (para frente e para trás), arrasto de trenó. Dependente da carga, estresse mínimo nas articulações, alta transferência de velocidade.

RemoTreinos intervalados no remo Concept2. Alta demanda metabólica, baixo impacto, desenvolve a resistência da cadeia posterior.

cordas de batalhaTrabalho dinâmico explosivo. Desenvolve simultaneamente a estabilidade do ombro e a capacidade de trabalho.

Bicicleta de assaltoCondicionamento com ênfase nas pernas. Desenvolve resistência muscular na parte inferior do corpo sem causar fadiga com a barra.

Pular corda e exercícios de movimentação dos pésExercício dinâmico para o corpo todo. Desenvolve a coordenação, a saúde das articulações e a vitalidade neural.

A treino de força dinâmica que integra estes exercícios de condicionamento Produz adaptações gerais superiores em comparação com o trabalho focado apenas na força.²

FAQs

1. Com que frequência por semana devo fazer treinamento de força dinâmico?

A pesquisa apoia de 2 a 4 pessoas dedicadas. rotinas de treinamento de força dinâmica A frequência de treinos semanais varia de acordo com a intensidade e o período de recuperação. Sessões com ênfase na parte inferior do corpo costumam ser programadas de 1 a 2 vezes por semana devido ao acúmulo de fadiga. Treinos na parte superior do corpo podem ser tolerados de 2 a 3 vezes por semana. O total de sessões semanais (força + condicionamento) não deve exceder 5 a 6 para a maioria dos atletas, sem comprometer a recuperação.

2. Os exercícios de condicionamento podem reduzir os ganhos de força?

Não, quando programado adequadamente. Pesquisas mostram que o condicionamento aeróbico realizado após o treino de força, em horários diferentes ou em dias de descanso, não interfere no desenvolvimento da força. No entanto, o condicionamento aeróbico excessivo (mais de 45 minutos por semana de atividade física de baixa intensidade e ritmo constante) pode atenuar as adaptações de força devido aos sinais crônicos de sobretreinamento.

3. Devo fazer exercícios de força dinâmica ou exercícios estáticos/isométricos?

Ambos têm sua função. Exercícios estáticos desenvolvem força em ângulos articulares específicos e são valiosos para indivíduos propensos a lesões. Mas pesquisas mostram claramente que movimentos dinâmicos produzem uma transferência funcional superior para o desempenho atlético. Dedique 80%+ do seu volume de treinamento a exercícios de força dinâmica, com trabalho isométrico como suplemento (10-20%).

4. Como sei se a intensidade do meu treino de força dinâmica é adequada?

Use os dados de velocidade. Se a velocidade da primeira repetição for consistentemente menor do que o esperado, a carga está muito pesada ou a recuperação é insuficiente. Se a perda de velocidade por série for menor que 10%, a carga provavelmente está muito leve. O aplicativo Spleeft torna isso objetivo — você não precisa adivinhar com base em como "se sente".“

5. Exercícios dinâmicos para a parte superior do corpo são mais difíceis de sobrecarregar do que exercícios para a parte inferior do corpo?

Não inerentemente, mas exercícios para a parte superior do corpo frequentemente demonstram maior sensibilidade ao acúmulo de fadiga porque a estabilidade do ombro exige muito do sistema neurológico. Isso significa exercícios dinâmicos para a parte superior do corpo Pode ser necessário um período de recuperação mais longo entre as séries ou um volume ligeiramente menor em relação ao trabalho da parte inferior do corpo para manter a qualidade. Novamente, o feedback da velocidade revela se a qualidade está se deteriorando.

Iván de Lucas Rogero

Desempenho Físico MSC e CEO SpeeftApp

Dedicado a melhorar o desempenho atlético e o treinamento de ciclismo, combinando ciência e tecnologia para gerar resultados.

Referências

Schoenfeld BJ. Mecanismos de hipertrofia muscular e sua aplicação ao treinamento de resistência. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857–2872.

Gonzalez-Badillo JJ, Sanchez-Medina L. Velocidade de movimento como medida da intensidade da carga no treinamento de resistência. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(5):347–352.

Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Bellon CR, Stone MH. A importância da força muscular no desempenho atlético. Medicina Esportiva. 2018;48(4):765–785.

Weakley J, Mann B, Banyard H, et al. Treinamento baseado em velocidade: da teoria à prática. Strength Cond J. 2021;43(2):31–49.

García-Ramos A, Pestaña-Melero FL, Padial P, Haff GG. Diferenças no perfil de carga-velocidade entre o supino na máquina Smith e o supino com barra livre. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(2):326–334.

Pareja-Blanco F, Rodríguez-Rosell D, Sánchez-Medina L, et al. Efeitos da perda de velocidade durante o treinamento de resistência no desempenho atlético, ganhos de força e adaptações musculares. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(7):724–735.

Aplicativo Spleft. Rastreamento de velocidade em tempo real para treinamento de força dinâmico. Disponível em spleeft.app. Permite o ajuste preciso da carga e o monitoramento da qualidade do movimento em todas as áreas. exercícios de força dinâmica Com feedback imediato sobre a velocidade de repetição e os limites de perda de velocidade.