If you coach long enough, you eventually hit that moment: two athletes on the same program, same percentages, same cues… and completely different bar velocities. One is flying, the other looks like they’re lifting in slow motion. The spreadsheet says they’re both at 80%, but your eyes (and their bar) are telling a different story.

That gap between the numbers on paper and the reality under the bar is exactly where velocity‑based training lives.

This guide is for the coach on the floor, the online coach behind the dashboard, and the lifter who wants to train smarter, not just harder. You’ll see how to incorporate velocity-based training step by step, how velocity-based training theory actually translates into day‑to‑day decisions, and how to turn that theory into a clean, repeatable velocity-based training application using tools like Spleeft App.

DOWNLOAD SPLEEFT APP NOW FOR iOS, ANDROID AND APPLE WATCH!

1. What Are You Really Doing When You Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training?

At its core, velocity‑based training (VBT) is brutally simple:

Use how fast the bar (or body) moves to decide how heavy, how much, and when to stop in a set.¹

Instead of guessing that “today 80% of 1RM is fine,” you use movement velocity as a live signal of how challenging that load is for the athlete right now. Decades of work on the load‑velocity relationship show that for a given exercise, there is a very tight correlation between relative load (%1RM) and mean concentric velocity when the athlete pushes with maximal intent.¹²

In practice, that means:

Heavier loads → systematically lower velocities

Lighter loads → higher velocities

Fatigue → velocities drop at the same load

Adaptation → you can move the same load faster, or a heavier load at the same velocity

Systematic reviews and meta‑analyses back this up: using VBT to autoregulate training has been shown to improve maximal strength, jump performance, and linear sprint performance in trained individuals, with effect sizes that are at least comparable—and often superior—to traditional percentage‑based programming.³⁴

So when you incorporate velocity-based training, you’re not adding a gadget. You’re changing the unit you use to make decisions—from “weight on the bar” to velocity under the bar.

2. From Velocity‑Based Training Theory to Application: The Three Core Pillars

There’s a lot of noise around VBT, but almost every effective velocity-based training application rests on three pillars:

Load‑velocity relationship

Velocity “zones” or ranges for different adaptations

Velocity loss thresholds inside a set

2.1 Load‑Velocity Relationship: Your Individual Map

For each key lift, if you measure velocity at several loads (say from ~40–85% 1RM), you’ll see a nearly linear drop in mean concentric velocity as load increases.¹² That’s your athlete’s load‑velocity profile.

You can use this to:

Estimate 1RM from submaximal work

Prescribe loads based on target velocity instead of fixed percentages

Track progress when 1RM testing is not desirable or safe

This is where an app like Spleeft App makes life easier: instead of exporting CSVs and plotting trends by hand, the app can log every rep’s velocity, estimate 1RM from your recent training, and update that load‑velocity profile as the athlete adapts.

2.2 Velocity Ranges for Different Strength Qualities

In velocity-based training theory, different ranges of mean concentric velocity tend to bias different adaptations—heavy, low‑velocity work favors maximal force; moderate‑velocity work favors power; very high‑velocity work skews toward elastic and ballistic output.³⁵

A simplified example (values vary by exercise and individual):

| Target Quality | Approx. Mean Concentric Velocity (m/s) | Typical Relative Load (ballpark) |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy strength | ≤ 0.40 | ≥ 80% 1RM |

| Strength‑oriented power | 0.40–0.70 | ~60–80% 1RM |

| High‑velocity power / ballistic | ≥ 0.70 | ≤ 60% 1RM |

When you incorporate velocity-based training, you stop thinking only in terms of “5×5 at 80%” and start thinking “3–5 sets in the 0.45–0.55 m/s range today.” If the athlete is more fatigued, the same load might drop out of that range quickly—so you reduce the load and keep the adaptation target instead of the original percentage.

2.3 Velocity Loss Thresholds: How You Control Fatigue

The third pillar is velocity loss: how much the rep velocity drops within a set compared to the fastest rep in that set.

Research from Pareja‑Blanco and colleagues has repeatedly shown that how much velocity you allow to drop in a set is a powerful controller of training stimulus and fatigue.⁵⁻⁷

Small velocity loss (≈10–20%) → lower fatigue, strong neural and strength gains, better explosive performance

Large velocity loss (≈30–50%) → more hypertrophy and endurance, but more fatigue and longer recovery

A simplified comparison:

| Velocity Loss per Set | Reps to Failure (roughly) | Main Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| ~10–20% | Far from failure | Strength, neural adaptations, freshness |

| ~20–30% | Moderate proximity | Strength + hypertrophy mix |

| ~30–40%+ | Close to failure | Hypertrophy, local fatigue |

A smart velocity-based training application lets you set these thresholds and cuts the set when the athlete hits that planned drop—exactly what Spleeft App is built to do in real time.

3. How to Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training as an Athlete

Let’s start from the lifter’s point of view. You’re training alone or following a remote plan. How do you incorporate velocity-based training without turning every session into a science experiment?

Step 1: Pick Your Main “Velocity” Lifts

Start with 1–2 big compound lifts where technique is stable:

Back squat or trap‑bar deadlift

Bench press or incline press

Horizontal row or chin‑up variation (if measured reliably)

Use VBT on those; everything else can stay percentage‑based or RPE‑based.

Step 2: Capture Baseline Velocity with Spleeft App

Over 1–2 weeks, during your normal training:

Open Spleeft App for your main lift

Warm up as usual, but record every working set

Always push the concentric phase with maximal intent (this is critical; studies show intent is a key driver of velocity‑specific adaptations).⁸

Spleeft will start building a picture of what your average velocities look like at your usual working loads, and it can estimate your 1RM from that data instead of requiring a dangerous test day.

Step 3: Start Using Velocity Ranges Instead of Just Percentages

On a “strength” squat day, instead of:

5×3 at 82.5% 1RM

You might go with:

5×3 in the 0.40–0.50 m/s range, cut the set if velocity drops by more than 20%

Practically:

Warm up into a load where your first rep is around 0.45 m/s

If rep 2 and 3 stay above ~0.36 m/s (20% drop from 0.45), that’s a good set

If you see 0.30–0.32 m/s on rep 3, that’s past your threshold—next set, reduce load slightly

Spleeft App handles the math and visuals, so all you see is:

“Rep 1: 0.46 m/s, Rep 2: 0.44 m/s, Rep 3: 0.39 m/s, Velocity loss: 15% → ✅ Set complete.”

Step 4: Let Velocity Guide Your “Go” vs “Grind” Days

Because velocity is sensitive to daily readiness, you can make simple rules for yourself:

If your usual working load is moving faster than normal, add a little load

If everything is slower than normal at your usual load, drop the load and stay in the planned velocity range

Research shows this kind of autoregulation via velocity allows athletes to get similar or better strength and power gains with less junk volume and better explosive performance.⁴⁻⁷

For a self‑coached athlete, this is the easiest point of entry: start tracking, then gradually let velocity ranges and loss thresholds refine your decisions.

4. How to Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training as an In‑Person Coach

Now, shift hats. You’re on the floor with 10–25 athletes, a tight time window, and limited attention. How do you build a velocity-based training application that’s realistic for this chaos?

4.1 Start with One or Two Anchor Lifts

For most field and court sports, that’s usually:

Back squat or front squat

Bench press or trap‑bar deadlift

For these anchors, you can:

Establish a simple load‑velocity profile over a few weeks

Decide on typical velocity ranges for “strength‑biased” vs “power‑biased” days

Use modest velocity loss thresholds (10–25%) to control fatigue in‑season

Frameworks for team‑sport VBT consistently recommend picking a small number of key lifts and embedding VBT into normal warm‑up and work‑set structure, rather than trying to “VBT‑ify” the entire program on day one.³⁹

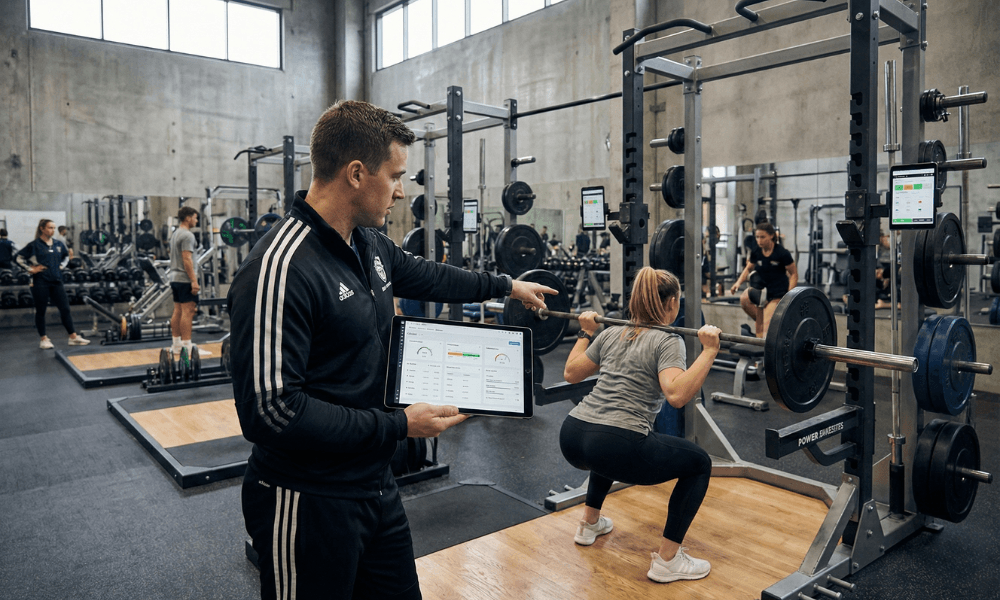

4.2 Use Spleeft App Stations for Live Feedback

A practical layout might be:

Racks 1–3: Equipped with Spleeft App running on tablets or phones

Every athlete logs into their profile on arriving at the rack

You set the day’s target (for example, “Squat: 0.45–0.55 m/s, 15% loss cap”)

Now your coaching loop becomes:

Watch the rep velocity pop up after each attempt

If a whole group is slow today → drop the planned loads a bit

If one athlete is chronically low in velocity for the same load vs peers → you have a red‑flag for fatigue, technique, or readiness

In large squads, this approach has been highlighted as a way to individualize training load without losing control of the group session.³⁹¹⁰

4.3 Example: Strength‑Biased vs Power‑Biased Block

For a 4‑week mesocycle, your squat progression might look like:

| Week | Focus | Velocity Range (m/s) | Velocity Loss Threshold | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Strength‑biased | 0.40–0.50 | ≤ 20% | Moderate volume |

| 2 | Strength‑biased | 0.35–0.45 | ≤ 20% | Slightly heavier loads |

| 3 | Power‑biased | 0.50–0.70 | ≤ 15% | Lighter loads, more velocity |

| 4 | Power‑biased / taper | 0.60–0.80 | ≤ 10% | Low volume, high freshness |

You don’t even need to show athletes the numbers if that overwhelms them. A color‑coded interface—like what you can set up in Spleeft App—can turn those zones into simple “green = good, red = stop” feedback.

5. How to Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training as an Online Coach

Online coaches live and die by data quality and communication. The good news: velocity is data‑rich. The bad news: data without structure is just noise.

Here’s how to turn VBT into a clean velocity-based training application for remote clients.

5.1 Standardize How Clients Use Spleeft App

From day one, give your remote athletes a simple protocol:

Always log prescribed VBT lifts in Spleeft App

Always use maximal intent on the concentric

Always film from roughly the same angle (if you want video checks)

Always sync their sessions before your weekly review

You can then look at:

Average velocities for key loads

How quickly velocity degrades across sets

Whether they consistently overshoot or undershoot your target ranges

5.2 Program by Velocity First, Percentage Second

Your remote squat prescription might look like:

Day A (strength):

4–5 sets of 3–4 reps

Target: 0.35–0.45 m/s, 15–20% loss cap

Day B (higher‑velocity power):

4–6 sets of 2–3 reps

Target: 0.55–0.70 m/s, ≤ 15% loss

Instead of arguing about whether they are really using 78% or 82%, you review the Spleeft data:

If their “strength day” averages look like 0.28 m/s → they are drifting too heavy / too fatigued

If their “higher‑velocity” day has a lot of sets at 0.40 m/s → loads are too heavy for the intended quality

You then coach primarily through the lens of velocity, sending notes like:

“Next week, start your working squats 5–10 kg lighter. I want your first rep closer to 0.60 m/s on the higher‑velocity sessions so we’re really biasing that quality.”

5.3 Comparing Use Cases: Athlete vs Live Coach vs Online Coach

A quick comparison of how each profile typically uses VBT and Spleeft:

| User Type | Main Goal with VBT | How They Use Spleeft App | Biggest Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athlete (self) | Train smarter, avoid unnecessary fatigue | Track key lifts, watch live velocities, adjust loads | Instant feedback, built‑in autoregulation |

| In‑person coach | Individualize in groups, manage fatigue | Set zones & thresholds, monitor racks in real time | Better control of group sessions |

| Online coach | Program precisely, monitor remotely | Review session logs & trends, prescribe velocity targets | Objective remote oversight |

For all three, the process of how to incorporate velocity-based training is similar—the difference is how much of the decision‑making is live vs asynchronous.

6. A Simple 3‑Step On‑Ramp to Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training

If you’re overwhelmed by the amount of velocity-based training theory out there, here’s a minimalistic on‑ramp that respects the science without drowning you in it.¹³⁴⁸

Step 1: Track Before You Change

For 2–3 weeks, add Spleeft App to your normal program on 1–2 lifts

Don’t change loads yet—just collect velocity and get athletes used to maximal intent

Note typical velocities at your bread‑and‑butter loads

Step 2: Add One Velocity Range and One Loss Threshold

Choose one lift (e.g., back squat) and one day (e.g., “main strength day”)

Define a realistic range (say 0.35–0.50 m/s) and a loss cap (15–20%)

Tell athletes: “Work up until your first rep is in this range, then do sets, stopping each set when you hit that loss cap.”

Step 3: Refine with Weekly Review

Each week, ask:

Are velocities drifting slower over time at the same load? → maybe too much volume or poor recovery

Are athletes able to handle heavier loads at the same velocity range? → clear sign of progress

Are some athletes consistently hitting much bigger velocity loss than planned? → tighten thresholds or coach technique

Within a month, you’ll have a functioning velocity-based training application that respects the underlying velocity-based training theory but feels intuitive on the floor.

7. Common Mistakes When You First Incorporate Velocity‑Based Training

Even good coaches trip over similar issues at first.

7.1 Chasing Numbers Over Movement Quality

Velocity is a signal, not the goal. If technique breaks down in the chase for higher velocities, you’re missing the point. Prioritize consistent technique, then use velocity as your guide inside that constraint.

7.2 Ignoring Contraction Intent

A key message from recent narrative reviews: explosive intent is at least as important as the exact movement velocity for driving velocity‑specific adaptations.⁸ If your athletes coast through reps, your velocity data will be noisy and your adaptations blunted.

7.3 Setting Overly Narrow Velocity Targets

Real reps fluctuate. If your target is “0.50 m/s exactly,” you’ll drive everyone crazy. Use bands (for example, 0.45–0.55 m/s) and focus on staying broadly in that zone.

7.4 Forgetting Exercise‑Specific Differences

A “heavy” velocity in bench press is not the same as in squat. Build exercise‑specific expectations by collecting data and reviewing them over time, rather than forcibly applying generic charts to everyone.

7.5 Not Educating Athletes

If athletes (or clients) don’t understand why you’re asking them to watch velocity and cut sets early, they may feel like they’re under‑training. A two‑minute explanation—”we’re protecting your freshness while still hitting the strength stimulus”—goes a long way.

8. FAQs

1. Can velocity‑based training be used for conditioning or only for strength work?

Yes, you can incorporate velocity-based training concepts into conditioning blocks, especially for team‑sport athletes. Instead of monitoring bar velocity, you might track movement velocity in sled pushes, jumps, or repeated effort med‑ball throws, and end the set or drill when velocity drops past a planned threshold. This keeps the quality of work high rather than letting sessions devolve into sloppy fatigue.

2. Is velocity‑based training useful for older or less experienced lifters?

Absolutely, with the right constraints. For older adults or novices, the main aim is often to develop force and power safely. Using conservative loads and monitoring velocity helps ensure they are moving with intent without drifting too close to failure. The objective feedback can also be motivating—seeing velocity numbers improve at the same load is a very clear sign of progress, even before maximal strength tests make sense.

3. How does velocity‑based training fit into a rehab or return‑to‑play process?

In rehab, you can use velocity as a ceiling rather than only a goal. For example, you might restrict bar velocity on certain exercises to avoid overly ballistic efforts in early stages, then gradually allow higher velocities as tissues tolerate more explosive work. Later, when re‑introducing heavier lifts, monitoring velocity and velocity loss can help ensure the athlete does not accumulate more fatigue than the medical / performance staff is comfortable with in a given session.¹⁰

4. Can I use VBT effectively with Olympic lifts?

Yes, but with nuance. Weightlifting derivatives (power clean, hang clean pulls, jump shrugs) lend themselves well to velocity tracking because they are inherently high‑velocity movements. Instead of obsessing over exact meters per second, many coaches use velocity primarily to ensure consistency across sets: if the bar is clearly moving slower than usual at a given load, they back off slightly to keep the session in the desired high‑velocity zone.

5. Do I need to “calibrate” my velocity measurements regularly?

If you’re using a consistent device and setup (such as the same phone + Spleeft App positioning in the rack), your priority is internal consistency rather than chasing some absolute lab‑grade number. Reproducibility studies show that modern velocity devices are typically reliable enough for day‑to‑day training decisions when used consistently in the same context.¹⁰ So, focus on using the same device, mounting, and camera angle each time, and treat velocity changes over time as the meaningful signal.

Iván de Lucas Rogero

MSC Physical Performance & CEO SpleeftApp

Dedicated to improving athletic performance and cycling training, combining science and technology to drive results.

References

Weakley JJS, Mann B, Banyard H, et al. Velocity-Based Training: From Theory to Application. Strength & Conditioning Journal.

GymAware. Velocity Based Training: theory and application. GymAware Blog, 2025.

Banyard HG, Nosaka K, Haff GG, et al. Effects of Velocity-Based Training on Strength and Power in Elite Athletes—A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

Chen YS, Wang YT, Lin CY, et al. The Role of Velocity-Based Training (VBT) in Enhancing Athletic Performance in Trained Individuals: A Meta‑Analysis of Controlled Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

Pareja‑Blanco F, Rodríguez‑Rosell D, Sánchez‑Medina L, et al. Effects of velocity loss during resistance training on athletic performance, strength gains and muscle adaptations. Scand J Med Sci Sports.

Pareja‑Blanco F, Alcazar J, Cornejo‑Daza PJ, et al. Effects of velocity loss in the bench press exercise on strength gains, neuromuscular adaptations, and muscle hypertrophy. Scand J Med Sci Sports.

Rojas‑Jaramillo A, et al. Velocity-Based Training in Soccer: A Brief Narrative Review with Practical Recommendations. J Func Morphol Kinesiol.

Behm DG, Konrad A, Nakamura M, et al. A narrative review of velocity-based training best practice: the importance of contraction intent versus movement speed. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab.

Orange ST, Metcalfe JW, Robinson A, et al. The Implementation of Velocity-Based Training Paradigm for Team Sports: Framework, Technologies, Practical Recommendations and Challenges. Sports.

Banyard HG, Tufano JJ, Delgado J, et al. Implementing a velocity-based approach to resistance training: the reproducibility and sensitivity of different velocity monitoring technologies. Sports Med Open.